Content - The Water Equation: More Than Just Zero

- Energy Footprint: The Fan vs. Pump Debate

- Material Longevity and Lifecycle Thinking

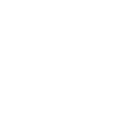

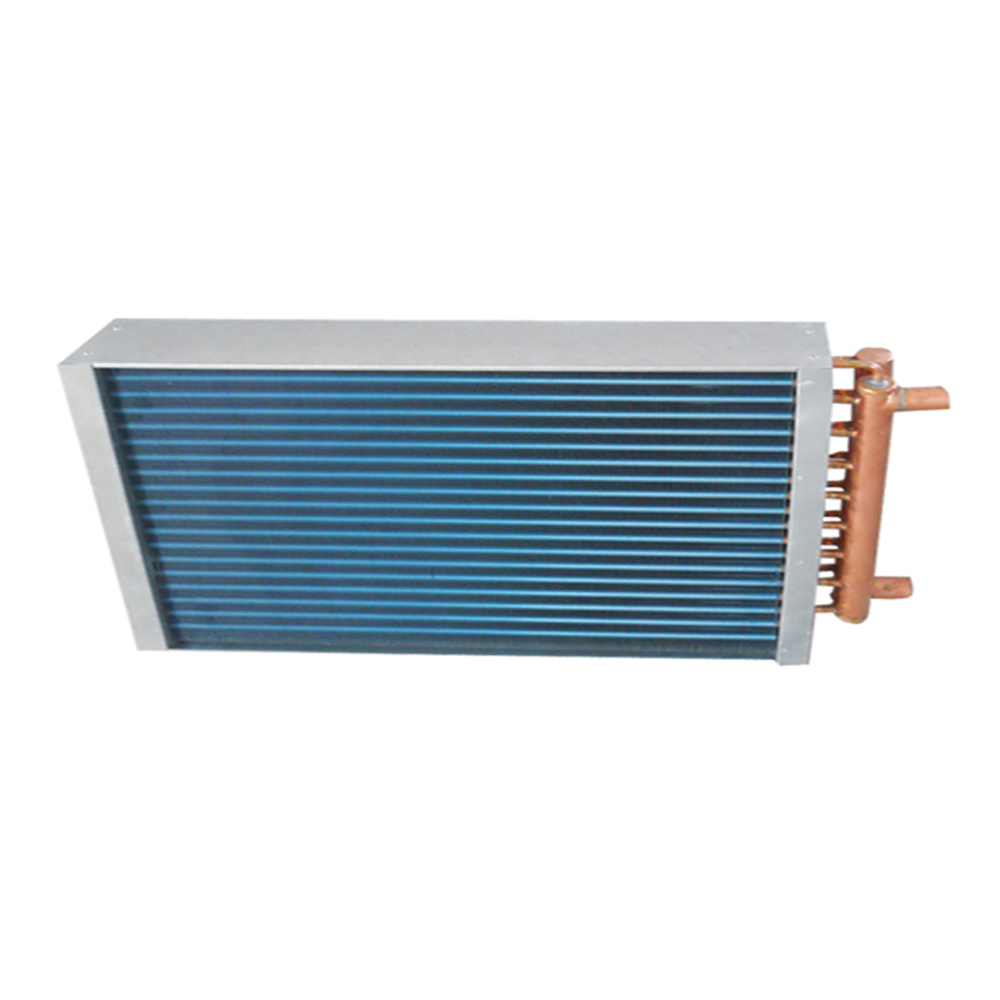

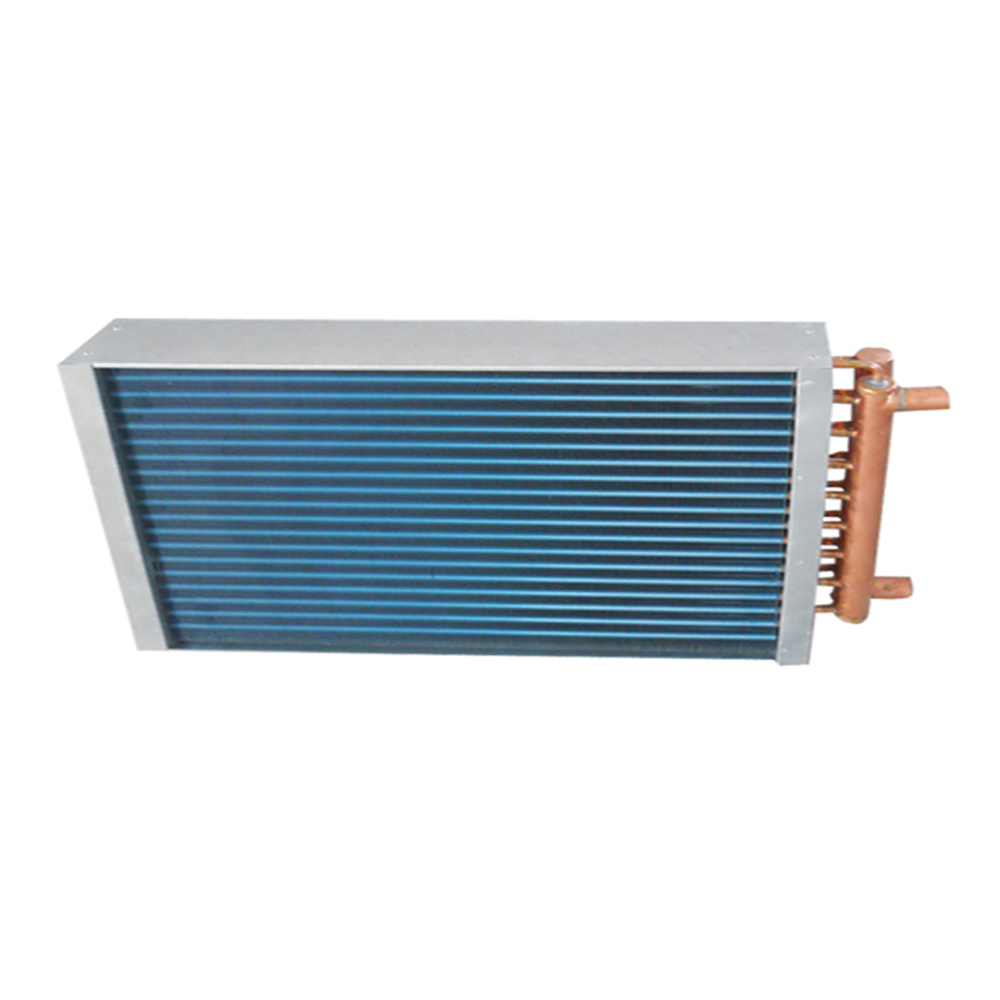

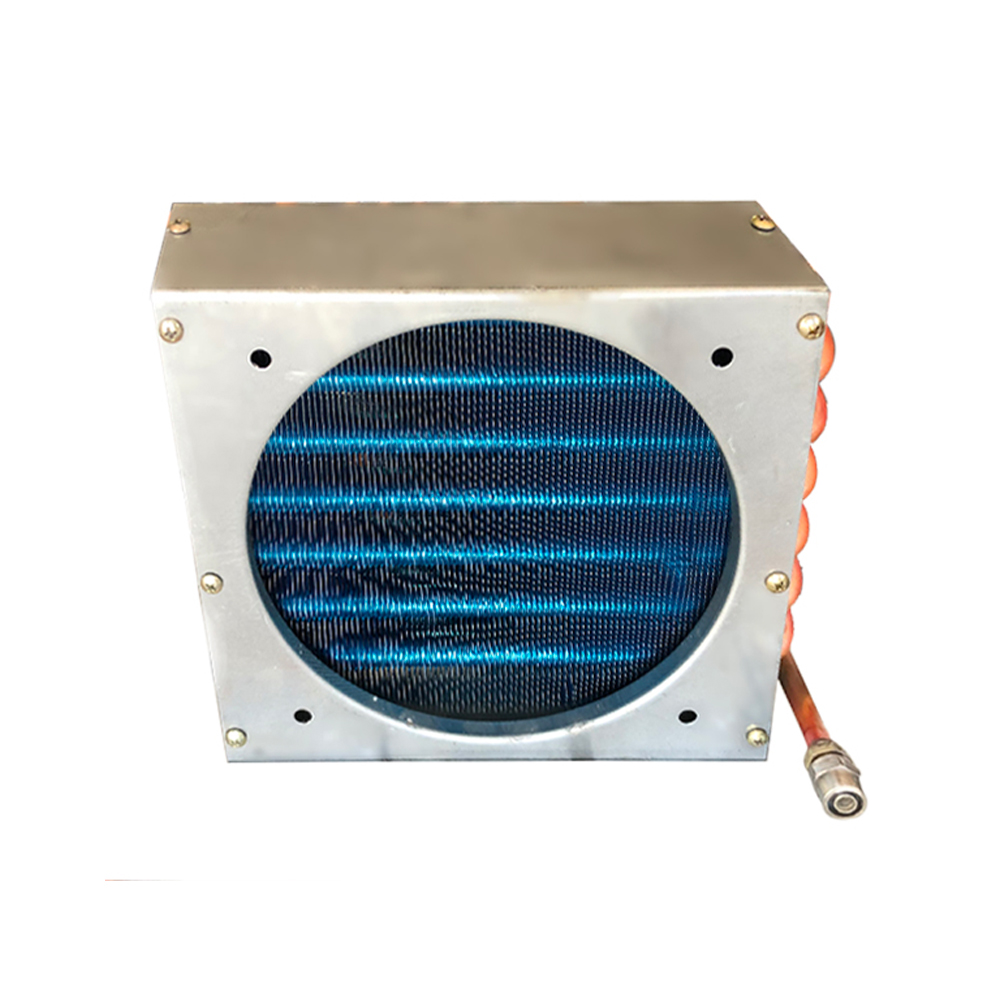

Sustainability isn’t just about operation; it’s about how long the hardware lasts and what happens to it. The core of an air cooled exchanger is the finned tube bundle. Corrosion is the enemy. In water systems, you fight internal corrosion and scaling. With ACEs, you’re battling external, atmospheric corrosion. This seems like a shift, not an elimination, of a problem. But in practice, it’s more manageable. You can select materials—like hot-dip galvanized steel fins or aluminum fins for specific services—that are suited to the local atmosphere. The lifecycle is often longer.

I remember inspecting 20-year-old ACE bundles in a refinery that were still in service with minimal degradation. A comparable water-cooled bundle would have been retubed at least once in that period. That retubing is a sustainability loss: mining more copper-nickel, manufacturing, transporting, and the energy for the repair work itself. The long service life of a robust ACE is a direct contribution to reduced material throughput. SHENGLIN’s emphasis on material science and coating technologies for different environments speaks to this deep industry understanding—it’s not just building a cooler, it’s building a durable asset.

End-of-life is also cleaner. An air cooler bundle is largely metallic and highly recyclable. There’s no contaminated sludge or complex material separation like in a failed water cooler bundle fouled with years of chemical deposits. At decommissioning, the steel and copper/aluminum get a second life easily.

Integration with Waste Heat Recovery

- The Real-World Compromises and Operator Buy-In

When you hear sustainability in heavy industry, minds often jump to solar panels or carbon capture. That’s a narrow view. The real, gritty work happens in optimizing the systems we already run 24/7. Take air cooled exchangers (ACEs). They’re not new tech, but their role in cutting water use and slashing operational waste is massively underplayed. I’ve seen projects where the obsession was with the headline-grabbing tech, while the humble air cooler, properly specified, did the heavy lifting for the plant’s environmental metrics. The link isn’t always direct, but it’s profoundly material.

The Water Equation: More Than Just Zero

Everyone knows ACEs eliminate cooling water. But the sustainability win isn’t just about hitting zero water discharge on a brochure. It’s about sidestepping the entire hidden cost chain of water. I’m talking about chemical treatment plants, blowdown management, and the energy hog that is the cooling water pump network. I recall a retrofit for a chemical processor in a water-stressed region. They were legally mandated to reduce draw. We swapped a bank of shell-and-tubes for an air cooled bundle. The immediate saving was millions of gallons annually, sure. But the bigger gain was decoupling their production capacity from local water politics. Their sustainability report got a line item, but their operational risk profile changed fundamentally.

There’s a catch, though. Air cooling isn’t a magic bullet for every process. Ambient air temperature is your driving force, and in hotter climates, you face a trade-off. You might need a larger face area or a hybrid setup. I’ve been involved in a project where this wasn’t adequately modeled. The ACEs were undersized for the peak summer temps, leading to slight process inefficiencies that initially offset some energy gains. We learned to always run annualized simulations, not just design-point calculations. The sustainability benefit is annual and cumulative, so your design must account for the worst and the best weather days.

This is where manufacturers with real field experience prove their worth. A company like Shanghai SHENGLIN M&E Technology Co.,Ltd, which focuses on industrial cooling tech, understands this. You can tell from their approach at shenglincoolers.com—it’s not just about selling a unit, but engineering a solution that fits the local climate and process duty. Their designs often incorporate variable speed drives on fans from the get-go, which is key for managing that energy-water trade-off intelligently.

Energy Footprint: The Fan vs. Pump Debate

The classic pushback is energy. Fans use more power than pumps, they say. It’s an oversimplification. Yes, moving air is less efficient than moving water per unit of heat transferred. But you’re comparing only the driver. A water-cooling system’s energy footprint includes the pumps, the water treatment plant, and the cooling towers. Those tower fans are massive consumers. When you sum it all up, a modern, well-designed air cooled system with optimized fin tubes and controlled fans can break even or come out ahead, especially when you factor in the eliminated water heating and treatment energy.

We proved this on a gas compressor station project. The initial design called for a water-cooling loop. When we did a full lifecycle energy analysis, the ACE option showed a 15% lower total energy cost over 10 years. The kicker? Most of the saving came from eliminating the constant chemical dosing and blowdown heating. The operators were skeptical until they saw the first year’s utility bills. The fans’ power draw was visible and easy to measure, but the myriad small loads of the water system had been invisible cost sinks.

Maintenance energy is another hidden factor. A water system requires constant vigilance against scaling and biofouling. That means maintenance shutdowns, chemical cleanings—all energy-intensive activities. An air cooler mostly needs keeping the fins clean. In dusty environments, that’s a task, but it’s predictable and often can be done online. The reliability directly contributes to sustainable operation by avoiding process upsets and the associated flaring or waste.

Material Longevity and Lifecycle Thinking

Sustainability isn’t just about operation; it’s about how long the hardware lasts and what happens to it. The core of an air cooled exchanger is the finned tube bundle. Corrosion is the enemy. In water systems, you fight internal corrosion and scaling. With ACEs, you’re battling external, atmospheric corrosion. This seems like a shift, not an elimination, of a problem. But in practice, it’s more manageable. You can select materials—like hot-dip galvanized steel fins or aluminum fins for specific services—that are suited to the local atmosphere. The lifecycle is often longer.

I remember inspecting 20-year-old ACE bundles in a refinery that were still in service with minimal degradation. A comparable water-cooled bundle would have been retubed at least once in that period. That retubing is a sustainability loss: mining more copper-nickel, manufacturing, transporting, and the energy for the repair work itself. The long service life of a robust ACE is a direct contribution to reduced material throughput. SHENGLIN’s emphasis on material science and coating technologies for different environments speaks to this deep industry understanding—it’s not just building a cooler, it’s building a durable asset.

End-of-life is also cleaner. An air cooler bundle is largely metallic and highly recyclable. There’s no contaminated sludge or complex material separation like in a failed water cooler bundle fouled with years of chemical deposits. At decommissioning, the steel and copper/aluminum get a second life easily.

Integration with Waste Heat Recovery

This is where it gets interesting. Air coolers are often seen as an endpoint—rejecting heat to the atmosphere. But with a shift in mindset, they become a facilitator for waste heat recovery. In many processes, the heat being rejected by an ACE is at a decent temperature grade. By designing the ACE not as a standalone unit but as part of a heat integration network, you can use it to pre-heat incoming process streams or even feed low-grade heat to absorption chillers.

We attempted this on a pilot scale at a petrochemical site. The overhead condenser from a distillation column, typically an ACE, was re-piped to first exchange heat with the column’s feed stream. This reduced the primary reboiler duty. The ACE then handled the remaining heat load. The project had teething problems—control was tricky because the air temperature variation now affected an upstream process parameter. It required smarter control logic, not just bigger hardware. It was a partial success, but it highlighted that the true sustainability leap comes from system thinking, not component swapping.

The key is to stop designing heat exchangers in isolation. The sustainability boost isn’t from the ACE itself, but from how it enables you to re-imagine the plant’s heat flow diagram. It’s a more flexible, air-based sink that can be strategically placed and sized to unlock pinch points that a rigid water network might not address.

The Real-World Compromises and Operator Buy-In

All this sounds good on paper, but the field dictates terms. Noise is a big one. A large battery of air cooled exchangers can be loud. Community noise regulations can force you to add attenuators or speed restrictions, impacting performance. I’ve seen a project where the beautiful, efficient ACE design had to be re-engineered with lower-speed fans and larger bundles to meet a 55 dB(A) limit at the fence line. The capital cost went up, and the energy efficiency dipped slightly. The sustainable choice had to balance technical performance with social license to operate.

Operator acceptance is another hurdle. Plant engineers who’ve spent their careers managing water chemistry and tower blowdown can be wary of a technology that seems to hand over control to the weather. The successful implementations always involved the operators early. We’d run workshops showing them the control screens, how to respond to a sudden rainstorm (which improves efficiency!), and how to clean the bundles. Making them part of the solution turned skeptics into advocates. Their daily practices—like keeping the fin banks clean—became a direct contribution to the plant’s sustainability goals.

Ultimately, air cooled exchangers boost sustainability by offering a pathway to simpler, more resilient, and materially efficient heat rejection. They force a discipline in design that considers full lifecycle costs and environmental context. They aren’t the right answer for every single duty, but where they fit, they don’t just reduce water use—they fundamentally rewire a plant’s relationship with its natural resource inputs. The boost is systemic, quiet, and over the long haul, transformative. It’s the kind of engineering that doesn’t make headlines but absolutely moves the needle.